By PharmD Live Staff Writer

The Social Determinants of Health in the African-American community include all of the factors of the U.S. Government’s Healthy People 2030, a set of data-driven national goals for improving health for all Americans. Included is a focus on the Merit-based Incentive Pay System (MIPS).

From poverty to food insecurity and violence, the history of racism can’t be ignored as a social determinant of health today. Enslavement established conditions that put little value on health, living conditions, and the people themselves.1 Hundreds of years later, the effects linger. Mistrust of the system based on objective and fabricated truths runs deep. Gaining trust among African American patients is a high hurdle that we must clear.

Louis Israel Dublin wrote in 1928, “An improvement in Negro health, to the point where it would compare favorably with that of the white race, would at one stroke wipe out many disabilities from which the race suffers, improve its economic status and stimulate its native abilities as would no other single improvement. These are the social implications of the facts of Negro Health.” 2

The entire U.S. medical system is fractured but especially affects African Americans and other underserved populations. Patients have multiple physicians and access to medications:

- Multiple prescriptions

- Samples

- Numerous pharmacies

- Over-the-counter drugs

- Herbal remedies and vitamins

In addition, the communication system to share analysis and the patient’s state is mediocre.

The confluence of these realities collides to create Adverse Drug Events, among other issues, with medical consequences for the patient’s health and cost to the patient, the system, and the economy.

The Federal Government’s effort to move Medicare and Medicaid from fee-for-service to quality-oriented Value-Based Care, the Merit-based Incentive Pay System (MIPS), separates those who must participate from those who are exempt. Since its introduction in 2017, physicians and clinicians have become more experienced in the rules and tools for transformation.

When the patient population is large but poor, this can be a blessing or a curse for African Americans and other underserved populations–if it doesn’t drive resources (i.e., hospitals and clinics) even further afield because of expense, rules, and regulations.2

Clinics with a stake in underserved or rural communities are familiar with the potential rewards and penalties associated with the new model. Some can’t afford to adopt the technologies that would help most, or the staff it takes to administer for compliance–or they are simply exempt. Yet, for larger population areas, participation is likely required.

How do we advance good health among African American communities through the health care system as it exists today?

With the population age 65+ growing, so are the number of chronic care management needs. The reality of mistrust and avoiding the medical community exacerbates the number and degree of chronic conditions in the African American population.

Chronic Care Management Services: A Bold Proposal

Pharmacists are being incorporated increasingly as clinical partners and are among the most trusted by patients in the medical field. Use these practitioners for their knowledge of the clinical setting. Use pharmacists for chronic care management.

PharmD Live® implements MIPS solutions for various health organizations, from private practices to ACOs. The ability to apply a pharmacist’s depth of pharmacological knowledge with its patented algorithm for flagging potential medical issues provides a means to participate in MIPS with success.

Chronic Care Management Services is another piece of the government quality initiative. A PharmD Live partnership can create financial stability for clinics that treat Medicare patients with two or more chronic conditions. For a clinic that operates on the slimmest of margins, the potential gain of a well-managed MIPS program in conjunction with a CCM program can support the financial needs of the clinic itself.

A closer look at chronic care management services

There are two Medicare programs at work within this disease management construct: Chronic Care Management and Remote Patient Monitoring.

The cost to a clinic is $0 for setting up the IT, patient management staff, tracking and collecting data with a PharmD Live plan in place. All Medicare patients who are eligible for the CCM and RPM programs are singled out for enrollment. Board-certified pharmacists (PharmD) coordinate all the interactions with patients and their primary care provider and any specialists.

Once armed with information about all medications and therapies earlier identified as part of the fractured system, pharmacists analyze the medical history and discuss with patients what drugs they take, and ensure they understand the role they play in making their treatment plan work.

Tens of millions of Americans have Low Health Literacy (LHL). As a percentage of the total African American population, nearly six in 10 have LHL compared to less than half that amount among non-Latin White Americans. Working one on one with a PharmD can help bring up the health literacy of these patients and engage them in their own well-being.

This entire process is tracked and coded by the pharmacist who monthly uploads an automated report to the clinic for reporting to CMS.

The targets set by CMS are included in the data platform the pharmacists use, and the broad number of quality targets used for achieving quality targets as a whole within the clinic are supplemented by the CCM and RPM reimbursement requests.

The financial and patient health upside of the MIPS tracking paired with the CCM and RPM reimbursements is demonstrable. Pharmacists should take their place among the efforts being made to meet and overcome challenges to good health for African Americans.

Citations:

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4580597. https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4#ref-CR14

- Dublin L. The health of the Negro. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1928;140:77–85. See also: Essay – Transforming American health care to improve end …. https://www.inmed.us/wp-content/uploads/Marginalized-African-American-People-Khalid-Eddahiri.pdf

Bibliography

What is Shortage Designation? https://bhw.hrsa.gov/shortage-designation/hpsas

Noonan, A.S., Velasco-Mondragon, H.E. & Wagner, F.A. Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: an overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Rev 37, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4 https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4#ref-CR14

Figures

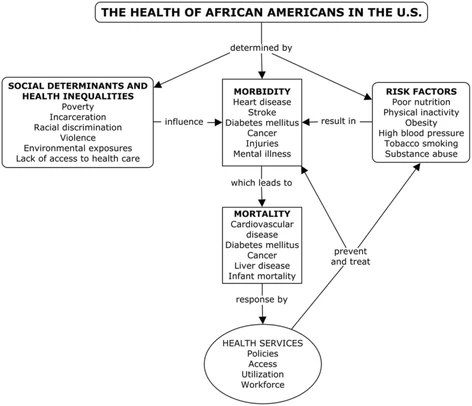

Fig 1. Noonan, A.S., Velasco-Mondragon, H.E. & Wagner, F.A. Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: an overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Rev 37, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4 https://publichealthreviews.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4#citeas